Free counterpoint

Part I - Free Counterpoint

Free counterpoint combines all the other species into one. In this type of counterpoint, one is able to have note-against-note, two against one, three against one, and four against one. Although not as common, it is possible to have two against three, and three against four.

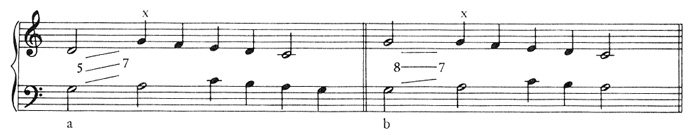

Fig.1 Free counterpoint

Notice that there exists 3:1 and 2:3, as well as 2:1 in this example.

Part II - Simple two-reprise Form

Also known as binary form, This most commonly exists as simple dance movements, Such as gigues1 or sarabandes2. Two-reprise pieces most commonly exist in sixteen, or twenty-four measures, The layout of the piece often looks like this:

||:8 measures:||:8 measures:|| and ||:8 measures:||:16 measures:||

Tonic Dominant Tonic Dominant

Even though the piece modulates for the second part, the overall feel of the piece does not shift (i.e. major/minor, tempo, etc.) Although the general feel of a piece does not change, it is normal to see a piece change tonality between the two sections.To facilitate this shift, the last measure of each section often tonicizes to the new tonic of the next section. Like this:

Major: minor:

||:I V(iii):|| ||:i v(V, or III):||

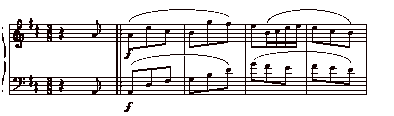

An example of the simple two-reprise form can be found in Bach's Minuet in d minor, BVW Anh.132

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Gigue: A lively dance piece of the Baroque and Renaissance, usually in compound meter.

2. Sarabande: A dance movement in triple meter (most commonly3/4, 6/8, and even 9/8)

||:8 measures:||:8 measures:|| and ||:8 measures:||:16 measures:||

Tonic Dominant Tonic Dominant

Even though the piece modulates for the second part, the overall feel of the piece does not shift (i.e. major/minor, tempo, etc.) Although the general feel of a piece does not change, it is normal to see a piece change tonality between the two sections.To facilitate this shift, the last measure of each section often tonicizes to the new tonic of the next section. Like this:

Major: minor:

||:I V(iii):|| ||:i v(V, or III):||

An example of the simple two-reprise form can be found in Bach's Minuet in d minor, BVW Anh.132

Notice that in the second part, the tonality shifts in the second part of the piece.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Gigue: A lively dance piece of the Baroque and Renaissance, usually in compound meter.

2. Sarabande: A dance movement in triple meter (most commonly3/4, 6/8, and even 9/8)